Accidents and a Horse - 1954

Dad drove the truck to the tree farm in the spring of 1954.

In June, Helen took the train to Kalispell and Missoula to visit. Norman went along.

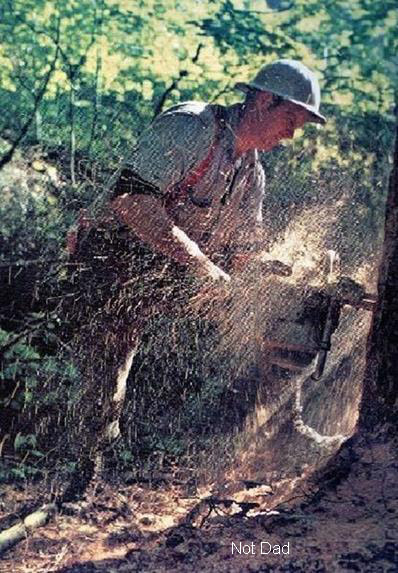

Norman stayed at the cabin and ‘helped’ with the tree cutting.

In June, Helen took the train to Kalispell and Missoula to visit. Norman went along.

Norman stayed at the cabin and ‘helped’ with the tree cutting.

Danger lurking and working in the woods

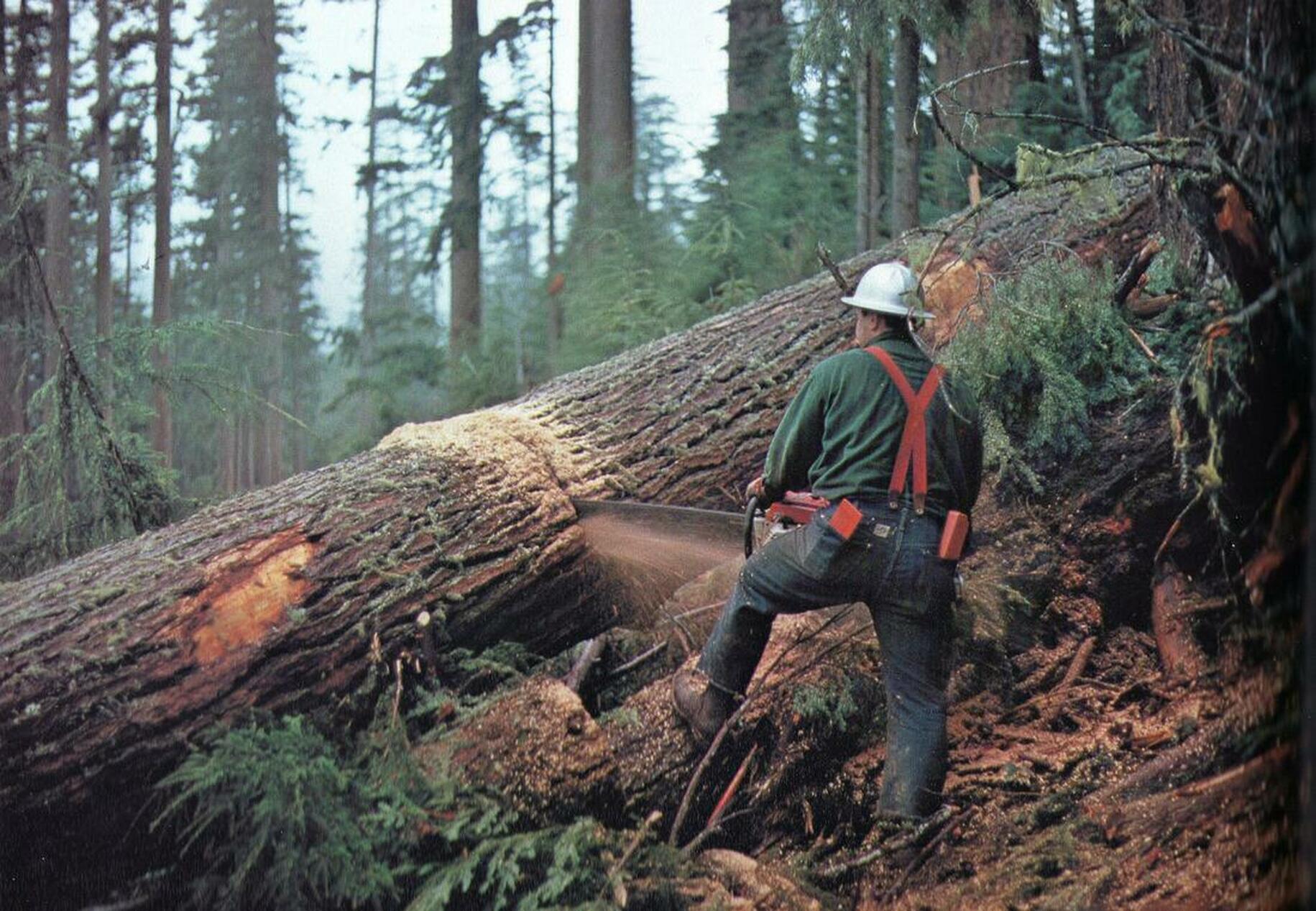

Dad’s logging activity nearly cost him his life. He was felling a large dying tree.

It fell between two crossed trees which made like a catapult and whipped one end

of the falling tree into his chest while he was holding the large, operating, chain saw.

He was knocked about 10 feet, and unconscious.

The 30 pound Titan 60 went another 10 feet, and got a dent in its stout handle.

Norman was about 100 feet away, and very confused.

Dad was not visible. The saw was quiet.

Norman began walking forward. After many seconds, Dad sat up in the tall grass.

As Norman was approaching, Dad slowly stood up.

Dad asked if he was bleeding. He was indeed cut and bleeding across the chin.

The next day he drove to Kalispell for a doctor exam.

That he would, 1) drive to town with an empty truck (no logs), and 2) visit a doctor,

were as much indications of the seriousness as was the accident itself.

He was pronounced as badly bruised and cut, but with nothing broken.

He cautiously returned to work the day after the doctor exam.

The chain saw retained the dent, but still cut through trees, loud as ever.

(Norman, then 10, still wonders what he would have done if this accident had been even worse.

Still doesn’t know.)

Norman stayed at the cabin while Helen continued to Missoula.

It fell between two crossed trees which made like a catapult and whipped one end

of the falling tree into his chest while he was holding the large, operating, chain saw.

He was knocked about 10 feet, and unconscious.

The 30 pound Titan 60 went another 10 feet, and got a dent in its stout handle.

Norman was about 100 feet away, and very confused.

Dad was not visible. The saw was quiet.

Norman began walking forward. After many seconds, Dad sat up in the tall grass.

As Norman was approaching, Dad slowly stood up.

Dad asked if he was bleeding. He was indeed cut and bleeding across the chin.

The next day he drove to Kalispell for a doctor exam.

That he would, 1) drive to town with an empty truck (no logs), and 2) visit a doctor,

were as much indications of the seriousness as was the accident itself.

He was pronounced as badly bruised and cut, but with nothing broken.

He cautiously returned to work the day after the doctor exam.

The chain saw retained the dent, but still cut through trees, loud as ever.

(Norman, then 10, still wonders what he would have done if this accident had been even worse.

Still doesn’t know.)

Norman stayed at the cabin while Helen continued to Missoula.

My job was to put the truck winch cable over one shoulder and a log choker chain over the other,

then walk into woods to the fallen tree. The farther I went, the heavier got the cable.

If I got close to the 200' maximum length, I was leaning in nearly 45°.

I would wrap (choke) the chain around the tree, hook the cable to it,

then pull the cable to the side as Dad winched in the slack till it was snug.

I was then required to move way to the side as the tree was dragged out of the forest.

A big tree snaking past the standing trees would 'whipsaw', 'fishtail' and roll unpredictably.

He hauled the horse 30 miles out to the tree farm on the open flatbed truck,

supported only by a stout rope from Fred's neck to the truck bulkhead.

The farmer assured that the horse had gone for rides before.

Dad was an experienced horseman and would drive with extra care,

and Fred was well versed in the laws of physics. He enjoyed the ride.

No one seemed concerned except the ten-year old kid, who spent most of the ride

watching out the back window, fearing the sight of the horse failing to negotiate a turn,

rolling off the truck, and then hanging over the side by the rope around his neck.

But Fred confidently assumed a wide four-point stance on his large hooves,

and used his huge neck as a lever against the rope, pressing in the direction opposite of the truck turning.

He looked back at me through the glass and seemed to say: "I'm having a nice ride, kid.

Why don't you turn around and watch where we're going?"

We first stopped at our neighbors, the Halverson’s, who had a loading ramp for their herd of cows.

I was still worried. Fred was bored.

He was turned around toward the back of the truck bed and carefully stepped down the ramp, one hoof at a time.

supported only by a stout rope from Fred's neck to the truck bulkhead.

The farmer assured that the horse had gone for rides before.

Dad was an experienced horseman and would drive with extra care,

and Fred was well versed in the laws of physics. He enjoyed the ride.

No one seemed concerned except the ten-year old kid, who spent most of the ride

watching out the back window, fearing the sight of the horse failing to negotiate a turn,

rolling off the truck, and then hanging over the side by the rope around his neck.

But Fred confidently assumed a wide four-point stance on his large hooves,

and used his huge neck as a lever against the rope, pressing in the direction opposite of the truck turning.

He looked back at me through the glass and seemed to say: "I'm having a nice ride, kid.

Why don't you turn around and watch where we're going?"

We first stopped at our neighbors, the Halverson’s, who had a loading ramp for their herd of cows.

I was still worried. Fred was bored.

He was turned around toward the back of the truck bed and carefully stepped down the ramp, one hoof at a time.

I was scared and yet realizing what a big lovable creature this was.

As Fred and I were entering the Turner Trees and crossing Red Owl Road,

Dad was walking our way to see if we were on course.

He seemed pleased that the horse and I were doing well. At least the horse was.

Fred was an interesting character study: he could stand for hours without moving -

"I'm in the shade, I've got water and oats up front and a fly swatter in the back - so why move?"

But when he was hitched up to a heavy fallen tree, this gentle giant would lean into the collar and

turn into a fire breathin' monster: Nostrils flared, teeth bared, eyes bulged.

He knew his job was to move that load and win the battle - then get back to standing still.

"I'm in the shade, I've got water and oats up front and a fly swatter in the back - so why move?"

But when he was hitched up to a heavy fallen tree, this gentle giant would lean into the collar and

turn into a fire breathin' monster: Nostrils flared, teeth bared, eyes bulged.

He knew his job was to move that load and win the battle - then get back to standing still.

I was sent down the hill to the corral to escort Fred up to the work area to start skidding out the cut trees.

I carelessly allowed the long rope to drag along on the ground.

Fred stepped on the rope, which pulled his head down slightly.

Like any good horse, he assumed he was now 'tied down' so he stopped and just stood there –

just like they do in the movies.

How to explain to a huge horse that he wasn't tied down - just standing on his own rope?

I tried to coax him to move to the side, or follow me, but he was 'tied' and couldn't move.

(I reflected later that maybe I could've tried pulling sideways on the rope, turning his head,

or stood off to the side, pretending I had food, or even tapping his leg to lift, like a blacksmith does.)

But he was happy to just stand there. I was getting worried: I was a failure as a cowboy.

But the big ol' horse was just out there in the woods with his new buddy: "So, what's the problem?"

After many minutes of this stand-off (stand-on?), Dad was coming down the trail,

obviously concerned about where I had gone with his new horse.

He explained the obvious: Don't let the rope drag on the ground.

Dad had been a Montana cowboy. He leaned into the horse, pushing on its head and neck.

This didn't move the horse, but sent the message: "Get off the rope!"

Fred probably thought: "Why didn't the kid just say so?"

The day's lesson: Coil the rope and carry it.

Hold on to the short end near the bit, just like real cowboys, and the horse will follow you anywhere.

I carelessly allowed the long rope to drag along on the ground.

Fred stepped on the rope, which pulled his head down slightly.

Like any good horse, he assumed he was now 'tied down' so he stopped and just stood there –

just like they do in the movies.

How to explain to a huge horse that he wasn't tied down - just standing on his own rope?

I tried to coax him to move to the side, or follow me, but he was 'tied' and couldn't move.

(I reflected later that maybe I could've tried pulling sideways on the rope, turning his head,

or stood off to the side, pretending I had food, or even tapping his leg to lift, like a blacksmith does.)

But he was happy to just stand there. I was getting worried: I was a failure as a cowboy.

But the big ol' horse was just out there in the woods with his new buddy: "So, what's the problem?"

After many minutes of this stand-off (stand-on?), Dad was coming down the trail,

obviously concerned about where I had gone with his new horse.

He explained the obvious: Don't let the rope drag on the ground.

Dad had been a Montana cowboy. He leaned into the horse, pushing on its head and neck.

This didn't move the horse, but sent the message: "Get off the rope!"

Fred probably thought: "Why didn't the kid just say so?"

The day's lesson: Coil the rope and carry it.

Hold on to the short end near the bit, just like real cowboys, and the horse will follow you anywhere.

Sometimes an extra-large tree proved to be the "immovable object" challenging Fred, the "irresistible force."

Fred didn't need to be encouraged to try harder.

He would 'hunker down' for better traction; step to one side, then the other,

searching for a better angle of attack; step back slightly, lifting his head high, then quickly pulling it down to add extra force, slamming into the collar, blowing steam, determined to move that load.

Fred didn't need to be encouraged to try harder.

He would 'hunker down' for better traction; step to one side, then the other,

searching for a better angle of attack; step back slightly, lifting his head high, then quickly pulling it down to add extra force, slamming into the collar, blowing steam, determined to move that load.

Dad watched closely for the 'point of no return,' when it was time to call off the horse,

to prevent him from being injured by his own valiant struggle.

It was both sad and inspiring to be watching when that big, strong beast had met its match,

but would refuse to surrender.

Belgians apparently were bred not only for the ability to pull the load,

but also with the fierce determination to win, even at the risk of injury.

The immovable heavy tree would have to be sawed into two sections.

This was a time-wasting and potentially costly move, since the field cut might fall

where it would compromise the minimum 8' cut necessary later for loading on the truck.

But it was much better than leaving all that lumber laying out in the woods.

to prevent him from being injured by his own valiant struggle.

It was both sad and inspiring to be watching when that big, strong beast had met its match,

but would refuse to surrender.

Belgians apparently were bred not only for the ability to pull the load,

but also with the fierce determination to win, even at the risk of injury.

The immovable heavy tree would have to be sawed into two sections.

This was a time-wasting and potentially costly move, since the field cut might fall

where it would compromise the minimum 8' cut necessary later for loading on the truck.

But it was much better than leaving all that lumber laying out in the woods.

While Dad went for the chainsaw, I would lead Fred far to the other direction and tie him to a tree.

(The chainsaw was screaming loud, and would cause much grief to even the calmest critter.)

Here Fred would quietly stand in place in his alternate role of big, friendly pet.

(The chainsaw was screaming loud, and would cause much grief to even the calmest critter.)

Here Fred would quietly stand in place in his alternate role of big, friendly pet.

Far away, Dad fired up the chainsaw. Fred jerked his head around: “What the hell was that?”

(The chainsaw is rated by OSHA as the worst of industrial products and processes that are painfully loud.)

When the big tree had been sectioned and the saw put away, I would lead Fred back into position

where he was re-hitched and then easily hauled out the divided enemy.

He seemed proud to have won the battle.

(The chainsaw is rated by OSHA as the worst of industrial products and processes that are painfully loud.)

When the big tree had been sectioned and the saw put away, I would lead Fred back into position

where he was re-hitched and then easily hauled out the divided enemy.

He seemed proud to have won the battle.

My summer visit was ending and I was about to go to the Halverson’s for a ride to Missoula.

I ran out to the corral to give Fred a goodbye pat on the neck.

He slimed me with a fat, sloppy tongue.

Fred was not a good kisser.

I ran out to the corral to give Fred a goodbye pat on the neck.

He slimed me with a fat, sloppy tongue.

Fred was not a good kisser.

The next season Fred was replaced by a Caterpillar Model 20.

It was not as nimble as Fred but could reach the entire property by pushing small trees out of the way.

It was not as nimble as Fred but could reach the entire property by pushing small trees out of the way.

It could skid out several trees at a time, and did not eat its weight in oats.

But it was much louder, chewed the ground into layers of dust, and was not as lovable.

But it was much louder, chewed the ground into layers of dust, and was not as lovable.

Thumbs Up

Norman cut his thumbnail nearly off on barbed wire when his hand slipped

while fastening the horse corral gate. (The flesh under a nail is very tender.)

The thumb was kept taped for several weeks while the barely attached nail finally grew out later that fall.

Can’t complain; it was the least serious medical problem that year.

Norman rode with some visitors of the Halverson’s to Missoula to rejoin Helen.

They then rode the Northern Pacific back to Spokane and Portland.

while fastening the horse corral gate. (The flesh under a nail is very tender.)

The thumb was kept taped for several weeks while the barely attached nail finally grew out later that fall.

Can’t complain; it was the least serious medical problem that year.

Norman rode with some visitors of the Halverson’s to Missoula to rejoin Helen.

They then rode the Northern Pacific back to Spokane and Portland.